Suppose we have a view camera and we wish to focus on a horizontal plane. More precisely, let the center of the lens \(O\) be \(a\) above the ground, and suppose the rear standard makes an angle \(\theta\) with respect to the horizontal. We wish to find the angle \(\alpha\) that the front standard must be tilted at to focus on the ground.

By the Scheimpflug rule. the rear standard, front standard, and horizontal intersect at a point \(S\). By the hinge rule, the front focal plane, the horizontal, and the plane through \(O\) parallel to the rear standard are concurrent; this is true if and only if the intersection point \(H\) of the horizontal and the plane parallel to the rear standard lies at a distance \(f\) from the front standard, where \(f\) is the focal length of the lens.

We have:

\begin{array}{lcl}

O'S = a / \tan{\alpha}\\

O'H = a / \tan{\theta}\\

SH = O'S - O'H = a(1/\tan{\alpha} - 1/\tan{\theta}) = a \left( \frac{\cos{\alpha}}{\sin{\alpha}} - \frac{\cos{\theta}}{\sin{\theta}} \right)

\end{array}

This means:

\begin{array}{lcl}

f = SH\sin{\alpha} = a\sin{\alpha} \left( \frac{\cos{\alpha}}{\sin{\alpha}} - \frac{\cos{\theta}}{\sin{\theta}} \right)\\

\frac{f}{a} = \cos{\alpha}-\frac{\cos{\theta}}{\sin{\theta}}\sin{\alpha}\\

\frac{f}{a}\sin{\theta} = \cos{\alpha}\sin{\theta} - \sin{\alpha}\cos{\theta} = \sin{(\theta-\alpha)}\\

\theta-\alpha = \arcsin{(\frac{f}{a}\sin{\theta})}\\

\alpha = \theta-\arcsin{(\frac{f}{a}\sin{\theta})}

\end{array}

In other words, the angle between the front and rear standards is \(\arcsin{(\frac{f}{a}\sin{\theta})}\). This is pretty neat; in particular, for small magifications we can say the ratio of of the sines of the angles is approximately equal to the magnification of the camera.

Sunday, September 3, 2017

Tuesday, August 22, 2017

Obligatory 2017 Eclipse GIF

Somehow this endeavor went better than planned, I was able to not only get to the site successfully and make it through traffic, but also get the tracking mount to track.

There was an "urp" moment when I fumbled and disconnected my A7II from the remote shutter app during totality, and another "urp" moment when I panicked and complete forgot about proper exposure times and such, but 1/80 turned out OK and the raw files have enough exposure latitude to do a bit of HDR if need be...

There was an "urp" moment when I fumbled and disconnected my A7II from the remote shutter app during totality, and another "urp" moment when I panicked and complete forgot about proper exposure times and such, but 1/80 turned out OK and the raw files have enough exposure latitude to do a bit of HDR if need be...

|

| A7II and Celestron C5 w/0.63x focal reducer (~750mm f/6.3), Spectrum glass filter, 1/80s ISO 100 |

Sunday, August 13, 2017

Super Plumbing

The cadet racing kart chassis we were working with had no front brakes. This was a problem, because our stopping power was already traction-limited at the rear wheels, and more time spent stopping meant less time accelerating.

Front brake conversion kits exist, but are rather expensive. Undaunted, we bought some generic moped calipers, proclaiming that "we'll figure out a way to mount them".

Ben came up with a pretty good way to mount them:

The stock direct spindle mount front wheels were replaced with a set of hub-mount rear wheels, and new hubs with 17mm bearings were made to mount them to the spindles. The arm that holds the caliper is centered using the precision-machined spindle shaft (which is the only precision surface in the kingpin assembly). Finally, a cross-piece is made which bolts to the arm and prevents it from rotating around the spindle.

Everything was made on the MITERS CNC (a mid-90's Dyna-Myte converted to LinuxCNC), and the mounts worked great.

The next step was to fill the brakes. Initial attempts were made to drive the two front calipers and the rear caliper (which had two pistons) using a single master cylinder:

This proved to be exceedingly unsuccessful; not only did the master cylinder have borderline displacement to drive four pistons, getting the air out of the loop and matching the piston travels proved to be nearly impossible. A day and a half into the ordeal, standards were lowered, and we decided to run the front and rear brakes off separate master cylinders actuated by a single pedal.

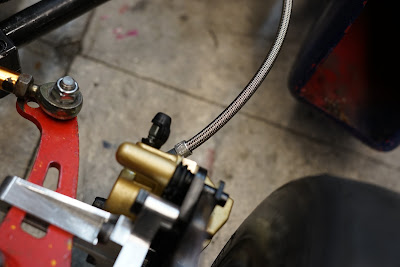

A word on the hoses: moped calipers take banjo bolts (hollow bolts sealed with crush washers). We used Earl's Performance braided lines to turn these into -3AN flares:

These connect to a 1/8" NPT tee:

The third arm of the tee is fitted with an NPT-to-compression adapter, which then goes to the master cylinder. A very unconventional setup, as compression fittings are not typically rated to brake line pressures. Go-karts get away with it with a combination of low pressures (hundreds, instead of thousands, of PSI) and short maintenance cycles (typically a couple dozen hours of runtime per season).

Front brake conversion kits exist, but are rather expensive. Undaunted, we bought some generic moped calipers, proclaiming that "we'll figure out a way to mount them".

Ben came up with a pretty good way to mount them:

The stock direct spindle mount front wheels were replaced with a set of hub-mount rear wheels, and new hubs with 17mm bearings were made to mount them to the spindles. The arm that holds the caliper is centered using the precision-machined spindle shaft (which is the only precision surface in the kingpin assembly). Finally, a cross-piece is made which bolts to the arm and prevents it from rotating around the spindle.

Everything was made on the MITERS CNC (a mid-90's Dyna-Myte converted to LinuxCNC), and the mounts worked great.

The next step was to fill the brakes. Initial attempts were made to drive the two front calipers and the rear caliper (which had two pistons) using a single master cylinder:

|

| Nope |

This proved to be exceedingly unsuccessful; not only did the master cylinder have borderline displacement to drive four pistons, getting the air out of the loop and matching the piston travels proved to be nearly impossible. A day and a half into the ordeal, standards were lowered, and we decided to run the front and rear brakes off separate master cylinders actuated by a single pedal.

A word on the hoses: moped calipers take banjo bolts (hollow bolts sealed with crush washers). We used Earl's Performance braided lines to turn these into -3AN flares:

The third arm of the tee is fitted with an NPT-to-compression adapter, which then goes to the master cylinder. A very unconventional setup, as compression fittings are not typically rated to brake line pressures. Go-karts get away with it with a combination of low pressures (hundreds, instead of thousands, of PSI) and short maintenance cycles (typically a couple dozen hours of runtime per season).

Wednesday, August 9, 2017

IPM Low-Speed Optimization

I had mentioned in a previous post that IPM's require both d and q-axis currents for optimal performance. Thanks to the motor equations, it is easy to quantify this split.

Recall that a sinusoidally-varying motor is modeled by:$$

\begin{array}{lcl}

\tau=\frac{3}{2}n_p(\lambda I_q+(L_d-L_q)I_d I_q)\\

V_d=R_s I_d-\omega L_q I_q\\

V_q=R_s I_q+\omega L_d I_d+\omega\lambda\\

V_s=\sqrt{V_d^2+V_q^2}\\

I_s=\sqrt{I_d^2+I_q^2}

\end{array}

$$ Suppose we have unlimited back EMF, and we wish to optimize torque per amp. There are two ways to look at this. Firstly, we could $$

\mbox{minimize }

\begin{cases}

I_d^2+I_q^2\mbox{ subject to}\\

\lambda I_q+(L_d-L_q)I_d I_q=\tau_0

\end{cases}

$$ Or, we could $$

\mbox{maximize }

\begin{cases}

\lambda I_q+(L_d-L_q)I_d I_q\mbox{ subject to}\\

I_d^2+I_q^2=I_0^2

\end{cases}

$$ As it turns out, the second current-first approach results in much easier math (we only need to solve a quadratic, not a quartic) at the expense of being somewhat less intuitive (it is unclear what current corresponds to what torque).

There are several ways to solve the second problem; we use Lagrange multipliers here. The Lagrangian is $$L(I_d,I_q,u)=\lambda I_q+(L_d-L_q)I_d I_q-u(I_d^2+I_q^2-I_0^2)$$ where \(u\), not \(\lambda\), is the multiplier.

The system of partial derivatives is $$

\begin{cases}

\frac{\partial L}{\partial I_d}=(L_d-L_q)I_q-2I_d u=0\\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial I_q}=(L_d-L_q)I_d-2I_q u+\lambda=0\\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial u}=I_0^2-I_d^2-I_q^2=0

\end{cases}

$$ This system is easily solved by a computer algebra system or by multiplying the first equation by \(I_q\) and the second by \(I_d\), giving $$

\begin{array}{lcl}

I_d=\frac{-\lambda+\sqrt{\lambda^2+8(L_d-L_q)^2I_0^2}}{4(L_d-L_q)}\\

I_q=\sqrt{I_0^2-I_d^2}

\end{array}

$$ where we have picked the signs knowing that \(I_d\) is negative and \(I_q\) is positive.

Armed with this information we can make some plots. Plugging in the HSG data \(L_d=0.0006\), \(L_q=0.0015\). and \(\lambda=0.053\) (units: Henries, Volt-seconds), we have the following plot:

As expected, \(I_d\) is about the same magnitude as \(I_q\) at high currents.

Recall that a sinusoidally-varying motor is modeled by:$$

\begin{array}{lcl}

\tau=\frac{3}{2}n_p(\lambda I_q+(L_d-L_q)I_d I_q)\\

V_d=R_s I_d-\omega L_q I_q\\

V_q=R_s I_q+\omega L_d I_d+\omega\lambda\\

V_s=\sqrt{V_d^2+V_q^2}\\

I_s=\sqrt{I_d^2+I_q^2}

\end{array}

$$ Suppose we have unlimited back EMF, and we wish to optimize torque per amp. There are two ways to look at this. Firstly, we could $$

\mbox{minimize }

\begin{cases}

I_d^2+I_q^2\mbox{ subject to}\\

\lambda I_q+(L_d-L_q)I_d I_q=\tau_0

\end{cases}

$$ Or, we could $$

\mbox{maximize }

\begin{cases}

\lambda I_q+(L_d-L_q)I_d I_q\mbox{ subject to}\\

I_d^2+I_q^2=I_0^2

\end{cases}

$$ As it turns out, the second current-first approach results in much easier math (we only need to solve a quadratic, not a quartic) at the expense of being somewhat less intuitive (it is unclear what current corresponds to what torque).

There are several ways to solve the second problem; we use Lagrange multipliers here. The Lagrangian is $$L(I_d,I_q,u)=\lambda I_q+(L_d-L_q)I_d I_q-u(I_d^2+I_q^2-I_0^2)$$ where \(u\), not \(\lambda\), is the multiplier.

The system of partial derivatives is $$

\begin{cases}

\frac{\partial L}{\partial I_d}=(L_d-L_q)I_q-2I_d u=0\\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial I_q}=(L_d-L_q)I_d-2I_q u+\lambda=0\\

\frac{\partial L}{\partial u}=I_0^2-I_d^2-I_q^2=0

\end{cases}

$$ This system is easily solved by a computer algebra system or by multiplying the first equation by \(I_q\) and the second by \(I_d\), giving $$

\begin{array}{lcl}

I_d=\frac{-\lambda+\sqrt{\lambda^2+8(L_d-L_q)^2I_0^2}}{4(L_d-L_q)}\\

I_q=\sqrt{I_0^2-I_d^2}

\end{array}

$$ where we have picked the signs knowing that \(I_d\) is negative and \(I_q\) is positive.

Armed with this information we can make some plots. Plugging in the HSG data \(L_d=0.0006\), \(L_q=0.0015\). and \(\lambda=0.053\) (units: Henries, Volt-seconds), we have the following plot:

As expected, \(I_d\) is about the same magnitude as \(I_q\) at high currents.

Tuesday, August 8, 2017

Plumbing Electrons

"Wiring is like plumbing, but for electrons"

-me, 2017

One of the things I've come to dread in any project is wiring. This particular wiring job is by no means stellar, but works well enough to be worth writing about.

Starting at the front:

The steering wheel controls consist of an e-stop and a key switch. The e-stop is wired in series with the +12V line going to the logic and by extension, the 12V supply for the internal gate drives on the power module. Hitting the e-stop shuts down the microcontroller and gate drive, which safely floats the inverter phases.

The key is wired in series with the 12V going to the contactor control line - contactor power does not go through the e-stop. As interrupting high DC link currents damages the contactor, this switch is intended to act as a last line of defense in case the inverter has failed short or otherwise stopped responding to gate drive. In normal fault situations (throttle failure, firmware error) the e-stop suffices.

From the steering wheel, two runs of McMaster 8082K37 shielded cable connect the switches to a power distribution board...

...which I swear is the only reason the go-kart thinks about working at all. The sketchy CNC'ed board replaces what would be an even sketchier mass of wire junctions.

The HV contactor is a Kilovac Csonka EV200:

The datasheet claims it is rated for dozens of interruptions at 500+A but I don't believe it. The precharge resistor is bolted directly across the contactor, which has the benefit of precharging the DC link capacitor whenever the HV connector is plugged in, and the downside of slowly draining the traction pack should the HV connector be left unplugged.

The motors are wired to the inverter via 10AWG silicone wire stuffed inside a copper braid finger-trap shield:

I am not convinced the shield is doing much (it isn't terminated on either end, and terminating it didn't seem to affect noise), but keeping the phase leads in as small of a bundle as possible is important for reducing radiated noise.The shield is sealed to the wire bundle with 3M EPS-300 adhesive backed heatshrink, which upon heating forms a tough, watertight seal glued to the shield and wires.

Moving back to the inverter:

The phase lead bundles are attached to the bus capacitor tabs by zip-ties. As much of the exposed bus bar as possible is covered in liquid electrical tape to reduce the chance of inverter-induced incidents.

The capacitor itself is mounted via standoffs and slotted tabs to the inverter block:

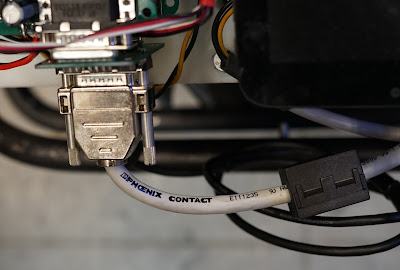

The image above also shows the power module control cable, which is cut short and terminated in a DB-15 connector, then run through a 20" commercial shielded DB-15 cable to the logic board:

The Phoenix Contact cable was irritatingly expensive (~$50 on eBay), but it was rather difficult to find good shielded 15-wire cable.

Finally, the throttle is actuated through a bowden cable attached to the original go-kart throttle pedal (which operated a mechanical throttle on a carbureted engine). The throttle sensor is a GM brake position sensor:

The bowden cable is crimped to a standard copper ring terminal; please don't do this for an actual brake! It is only acceptable here because a cable failure causes the throttle to return to an off-position.

Sonata Pack Module Testing

|

| I'd upload a 3-angle view if Blogger had a working gallery function |

This pack is quite aged, showing only 4Ah out of the 5.3 rated amp-hours.

However, pack impedance is promising, hovering between 10 and 15mohm for most of the SOC - not bad at all for a 5.3Ah 8S pack.

The module under test was also extremely well-balanced:

As would be expected from an automotive vendor with access to millions of cells.

The conclusion: you probably want an A-grade pack, but a B-grade pack is completely usable, albeit with degraded performance.

The Motor Equations

We are all taught as wee seedlings that motors, brushed or brushless, are governed by the following equations: $$

\begin{array}{lcl}

\tau=K_t I\\

\omega=K_v V\\

K_t = 1/K_v

\end{array}

$$ To a very rough approximation, these equations are true, and for hobby motors they work quite well. RC vendors usually quote \(K_v\) as the RPM per DC link voltage under trapezoidal commutation.

The above equations model the motor as a speed-dependent voltage source. However, a motor has both inductance and resistance as well. Taking a moment to blatantly ignore the definitions of 'inductance' and 'resistance' (there are several, depending on your conventions), a more accurate voltage equation might be: $$V = \omega/K_v+IR+n_p \omega L$$ Note the intentional lack of subscripts on \(R\) and \(L\); this equation is meant to be heuristic and should not be used to actually compute back EMF.

The motor equations

Taking into account inductance, resistance, and saliency, the complete equations describing a sinusoidally-varying motor with sinusoidal commutation are: $$\begin{array}{lcl}

\tau=\frac{3}{2}n_p(\lambda I_q+(L_d-L_q)I_d I_q)\\

V_d=R_s I_d-\omega L_q I_q\\

V_q=R_s I_q+\omega L_d I_d+\omega\lambda\\

V_s=\sqrt{V_d^2+V_q^2}

\end{array}

$$ Where \(R_s, L_d\) and \(L_q\) are the resistance and inductance of one phase, \(V_s\) is the peak AC stator voltage across one phase (which for standard SVM is equal to half the DC link voltage), \(\lambda\) is the PM flux linkage, and \(n_p\) is the number of pole pairs. \(I_d\) and \(I_q\) are the usual FOC axis currents.

These equations immediately tell us that IPM's (which have \(L_d < L_q\)) require current on both the d and q-axes to generate the highest torque. This is in stark contrast to SPM's, which typically want \(I_d=0\). On some IPM's, the reluctance component (\((L_d-L_q)I_d I_q\)) is very significant; e.g. for the Hyundai HSG we have \(\lambda=0.053\), \(L_d=0.6 mH\), and \(L_q=1.47 mH\). For high currents, reluctance torque is a huge fraction of the resulting torque...

...as evidenced by this stall test plot, where phase is practically equal to \(3\pi/4\) (the point of highest reluctance torque for a given stator current) at very high currents. This is because reluctance torque grows as the square of current, but PM torque grows only linearly.*

Next time, we will compute the optimum split between the d and q-axis currents for a motor at low speed (one which is not voltage-limited).

*only approximately true because of saturation, but empirical evidence shows it almost works!

\begin{array}{lcl}

\tau=K_t I\\

\omega=K_v V\\

K_t = 1/K_v

\end{array}

$$ To a very rough approximation, these equations are true, and for hobby motors they work quite well. RC vendors usually quote \(K_v\) as the RPM per DC link voltage under trapezoidal commutation.

The above equations model the motor as a speed-dependent voltage source. However, a motor has both inductance and resistance as well. Taking a moment to blatantly ignore the definitions of 'inductance' and 'resistance' (there are several, depending on your conventions), a more accurate voltage equation might be: $$V = \omega/K_v+IR+n_p \omega L$$ Note the intentional lack of subscripts on \(R\) and \(L\); this equation is meant to be heuristic and should not be used to actually compute back EMF.

The motor equations

Taking into account inductance, resistance, and saliency, the complete equations describing a sinusoidally-varying motor with sinusoidal commutation are: $$\begin{array}{lcl}

\tau=\frac{3}{2}n_p(\lambda I_q+(L_d-L_q)I_d I_q)\\

V_d=R_s I_d-\omega L_q I_q\\

V_q=R_s I_q+\omega L_d I_d+\omega\lambda\\

V_s=\sqrt{V_d^2+V_q^2}

\end{array}

$$ Where \(R_s, L_d\) and \(L_q\) are the resistance and inductance of one phase, \(V_s\) is the peak AC stator voltage across one phase (which for standard SVM is equal to half the DC link voltage), \(\lambda\) is the PM flux linkage, and \(n_p\) is the number of pole pairs. \(I_d\) and \(I_q\) are the usual FOC axis currents.

These equations immediately tell us that IPM's (which have \(L_d < L_q\)) require current on both the d and q-axes to generate the highest torque. This is in stark contrast to SPM's, which typically want \(I_d=0\). On some IPM's, the reluctance component (\((L_d-L_q)I_d I_q\)) is very significant; e.g. for the Hyundai HSG we have \(\lambda=0.053\), \(L_d=0.6 mH\), and \(L_q=1.47 mH\). For high currents, reluctance torque is a huge fraction of the resulting torque...

...as evidenced by this stall test plot, where phase is practically equal to \(3\pi/4\) (the point of highest reluctance torque for a given stator current) at very high currents. This is because reluctance torque grows as the square of current, but PM torque grows only linearly.*

Next time, we will compute the optimum split between the d and q-axis currents for a motor at low speed (one which is not voltage-limited).

*only approximately true because of saturation, but empirical evidence shows it almost works!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)